Higher rates to stay, though policy divergence won’t

By Vanguard

Markets and economy

The U.S. Fed is unlikely to cut rates in 2024. What does that mean for other regions?

Despite the twist presented by an unexpectedly strong U.S. economy, developments in the first half of 2024 have only strengthened our view that a higher-interest-rate environment is here to stay.

Vanguard’s regional chief economists—Roger Aliaga-Díaz for the Americas, Jumana Saleheen for Europe, and Qian Wang for the Asia-Pacific—discuss the implications of a brewing global policy-rate divergence and the role of a higher neutral rate in this environment.

Vanguard views it as unlikely that the Federal Reserve will start cutting rates this year. What does that mean for other regions?

Saleheen: Other central banks’ policy decisions will primarily be determined by each country’s economic and financial conditions. But in a globally interconnected world, other central banks cannot ignore the impact that the Fed—the central bank for the world’s largest economy—has on global financial conditions.

Europe is facing a very different environment than the U.S. Both the euro area and the U.K. flirted with recession in late 2023 before returning to growth in the first quarter of this year. The European Central Bank (ECB) has made the first of what we expect to be three rate cuts this year. But that brings its own complications. With rates going down in Europe, investors will want to keep their money in the U.S. because they get a higher return. This pushes up the value of the dollar and pushes down the euro, which in turn increases inflationary pressures for Europe, partly offsetting the stimulus benefits of rate cuts—it’s classic Econ 101. This is a constraint, but not enough to dissuade the ECB from making further cuts.

Wang: Those dynamics apply even more in emerging markets. Higher interest rates in the U.S. and a stronger dollar reduce capital inflows and increase the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt, and most of emerging markets’ debt is in dollars. Emerging markets tend to keep their interest rates above those of the Fed to stop capital outflows. Even if macro conditions suggest emerging markets should be cutting rates, they often can’t afford to do so before the Fed. In fact, Bank Indonesia raised rates again in April to counter currency depreciation. On the other hand, many emerging markets in Europe and Latin America started hiking rates well before the Fed, so they have leeway to cut rates as inflation cools and growth moderates. Central banks in Latin America have been doing so for several months.

China, meanwhile, would like to cut interest rates, and it should, because domestic demand is so weak and supply is abundant. But China still faces deflationary pressures and feels constrained by the Fed, with depreciation pressure on the renminbi. We still expect China’s central bank to cut rates, but not by as much as it otherwise might and perhaps later than planned because of the Fed staying on hold. Japan is an outlier in the global easing cycle, as it just ended its negative-interest-rate policy in March. Now the Bank of Japan is on a gradual path to normalisation given rising confidence in the sustainability of wage growth and inflation, as well as concerns about imported inflation.

Australia may end up being the last developed market to cut rates, as it is increasingly concerned about whether it can bring inflation back to target next year.

Aliaga-Díaz: The Bank of Canada was the first G7 central bank to start cutting rates. Similar to the euro area, this presents potential challenges to the Canadian economy with the Fed maintaining its higher-for-longer stance. This is even more true for Canada than for Europe, given the significance of the country’s trade and financial ties with the U.S. There is no “first-mover advantage” here. On the contrary, first movers find themselves in a tough spot as the weakening of the domestic economy means that they don’t have the luxury to wait and sync up with the Fed.

How are different central banks most likely to approach policy interest rates?

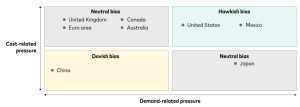

Wang: How central banks set policy will depend on their assessment of the source of inflation in their respective countries and whether it’s driven by demand or supply shocks. We assess this by considering the evolution of cost and demand pressures relative to the pre-COVID trend. The U.S. and China are hawkish and dovish, respectively, but most other countries would fall under what we would call the “neutral bias” category. These countries are ready to make rate cuts—or hikes in Japan’s case—or have already started doing so, but potentially at a slower pace than what otherwise might be warranted given expectations for the Fed. These countries are ready to change course if needed, depending on the incoming data.

Central banks constrained by inflationary pressures and Fed policy

Notes: The chart quadrants denote where each country is in terms of demand- and supply-side inflationary pressures relative to pre-COVID trends. Data from the fourth quarter of 2013 through the fourth quarter of 2019 were used to calculate pre-COVID trend growth rates. Demand-related pressure is measured as private services consumption relative to the pre-COVID trend. China’s consumption gap is measured using total private consumption of goods and services. Cost-related pressure is measured as unit labour costs relative to the pre-COVID trend.

Sources: Vanguard calculations using data as of March 31, 2024, from Eurostat, Bloomberg, the World Bank, the OECD, Datastream, and the St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED database.

Is it unusual for other central banks to cut rates before the Fed?

Aliaga-Díaz: Typically, other central banks take cues from the Fed given the implications of U.S. dollar flows for the stability of local currencies. A strong dollar may lead to higher domestic inflation, reduced foreign investment flows, and balance sheet mismatches between local-currency assets and hard-currency debt. Central banks are usually better off staying in lockstep with the Fed, but this time around, the U.S. is so different compared with the rest of the world. The U.S. economy has been so strong that it has forced the Fed to stay at its peak rate for the cycle for longer. Other central banks cannot delay policy normalisation much longer given domestic economic weakness.

Saleheen: The Fed is normally seen as much more activist than any other central bank. It is normally the first to take action to turn the cycle. But that’s in cases where there’s a common shock, and this period is unusual. While some shocks have been common, others have been specific to a country or region. In Europe, shocks have been centred around the war in Ukraine and higher energy prices, which have also affected emerging markets. But in the U.S., it’s a different set of shocks, much more related to strong demand, partly a result of fiscal stimulus and a resilient consumer.

How long do we expect monetary policy to diverge?

Aliaga-Díaz: The theme of central bank divergence has been a bit overstated in the markets, and it may not be as big of a challenge as commonly thought. While there may be a widening gap in the timing of first cuts, with the ECB and Bank of Canada starting in June and the Fed unlikely to cut before year-end, we don’t see a divergence in the projected path of central bank rates over the next few years. Once the Fed starts cutting rates, most major central banks will be moving in lockstep, with policy rates moving in the same direction.

Monetary policies likely to diverge only temporarily

Notes: Monthly data from January 2005 through June 20, 2024, and forecasts thereafter.

Sources: Vanguard calculations using data as of June 20, 2024, from Bloomberg and Macrobond.

Saleheen: This is not like the 2008 global financial crisis, when the Fed went down to zero very quickly and Europe didn’t act for another year or two. What we’re seeing now is more of a temporary divergence in monetary policy. It might be a matter of five or six months.

Wang: The key point is that we’re aligned in direction—just the timing is not in sync at the moment.

Vanguard believes that real interest rates aren’t going back to zero. Why is that?

Saleheen: We’ve been saying for more than a year that rates are not going back to zero. It’s a different world. The neutral rate, also referred to as R-star, is higher than it was pre-COVID.

Aliaga-Díaz: This touches on our “return to sound money” theme in our 2024 economic and market outlook. Bond interest rates are outpacing inflation for the first time in many years, which is good news for long-term investors. This is happening, we believe, because R-star has become higher. R-star is the equilibrium level of interest rates toward which central banks try to converge. This level is not determined by monetary policy, but instead is driven by demand of capital, or borrowing, and supply of capital, or savings. Due to demographic factors and government debt levels that may remain for years to come, we may have entered a period of persistently higher interest rates.

Saleheen: The fact that we’ve avoided a global recession means central banks are able to move interest rates from restrictive territory directly to neutral, side-stepping the need to drop interest rates down to stimulative territory. This has certainly helped the “R-star is higher” narrative become a mainstream view.

Aliaga-Díaz: For a while, financial markets have been pricing in a policy-rate landing point that is not far from our own projections. However, some central banks have been slower to acknowledge changes in R-star in the past, and we expect that it may take longer for them to recognise a higher R-star this time around. The Fed has nudged its R-star view modestly higher in its last two sets of economic projections. The problem in moving too slowly is that it can potentially lead to miscalibrations in monetary policy and slow progress against inflation.

What else should investors consider this year?

Saleheen: The current economic cycle is not a normal one. The global economy is still settling down after unprecedented economic shocks that include a pandemic, a war in Ukraine, and heightened geopolitical tensions. Structural changes such as an ageing population and the rising upward trend of fiscal debts also make it hard to decipher the economic cycle from the trend. This makes for a challenging environment for central banks, markets, and investors.

Wang: There are also uncertainties surrounding elections around the world that can determine fiscal policies, terms of trade, and so on. This is poised to be the largest global election year in history, affecting nearly half the world’s population. The unusually high level of political uncertainty, on top of two wars and other geopolitical risks, means we should brace for potentially higher market volatility in the coming months. We can’t predict the future, but we can ensure that our investments reflect both our goals and our time horizons to be confident we can ride out periods of volatility.

Aliaga-Díaz: You also have to wonder whether U.S. exceptionalism can continue or if the U.S. economy will eventually go through a needed slowdown to bring down inflation and converge with the rest of the world. As much as the U.S. economy and markets have outperformed, this is a critical time to think about global diversification and maintaining a well-diversified, balanced approach.